It’s interesting that we call this parable the parable of the Prodigal Son. The story does seem to revolve around him, but as Klyne Snodgrass mentions in his book Stories with Intent, there are other players here. He suggests (as do many scholars) that we should call it the Parable of the Compassionate Father and His Two Lost Sons instead. That seems to convey more of what is happening here. Though all of us seem to be able to compare ourselves to the Prodigal Son, sometimes we need to look at the other people involved and ask who am I really in this story? Am I the one who fell away from the faith, with a need to work my way back, counting on the mercy of our Father? Yes, sometimes indeed that is who I am. Am I also the elder sibling who instead of joy respond with anger and disgruntled feelings at the mercy that God is showing someone else? Sadly that sometimes describes me too. How about being like the Father, running out with compassion and grace to those who have wronged me?

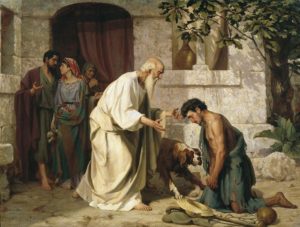

That’s a hard thing for us to ponder. The father by Jewish law not only had the right to disown his son for what he had done, but the son could also be put in prison for his actions. Here was the child who had said: “You’re dead to me.” Those are harsh things to receive from a child. Any parent who has had the experience of their child saying “I hate you.” or “I just wish you would go away” knows how it feels. Most of us know too what it would feel like to see them coming back after so long without them. I haven’t been back to Virginia in many years. My mom and dad can’t afford to travel up here, and I haven’t been able to get down there. I can only imagine what that must be like. To see your loved one in the distance, to run out to them and celebrate. To see the child who said “I hate you, die already” coming back and saying “I am sorry for what I did.” This is the kind of repentance that should accompany confession — getting over our pride and ego, coming back to the feet of God and begging for His mercy.

Then we also have the older brother who is in stark contrast to the rest of the village, servants, and family members. We don’t think about them much do we? They are inside already setting up the celebration, waiting for the Father and Sons to arrive. That’s the proper response for us, isn’t it? That when seeing that God’s kingdom is revealed in some small way before us we rejoice and celebrate. Do we always do that though? Are we inside celebrating? Or outside muttering about this or that? I find that politics right now seem to turn most of us into that other son. Instead of looking to find ways to help others to the feast, we justify some of our prejudices and hates on borders and political ideologies. Instead of inviting the widow, the orphan and the refugee to the feast to dine with us, we stand outside the wall labeling them the other.

How do we reconcile the two? Being both the prodigal ourselves and the brother outside? By looking for prodigals to run out to and accept with open arms. That doesn’t mean becoming a doormat. Nor does that mean that we shouldn’t have any sort of national security, that would be foolish. What it does mean is that we look to show dignity and respect to all people, regardless of their choices, lifestyle, or country of origin. Only then can we be inside at the feast waving for everyone to come in, getting the dinner ready for everyone else. That’s the job we want to have. Inviting to the banquet and joining in with the festivities. We Christians are often not a joyful lot… we should be. After all, if what we believe is true, then God is saying to us as well “My son, you are here with me always; everything I have is yours.” Now it’s time for us to find those family members who are out there lost in the fields of the world, squandering their inheritance and help them find their way back to the feast. There is more than enough to share.